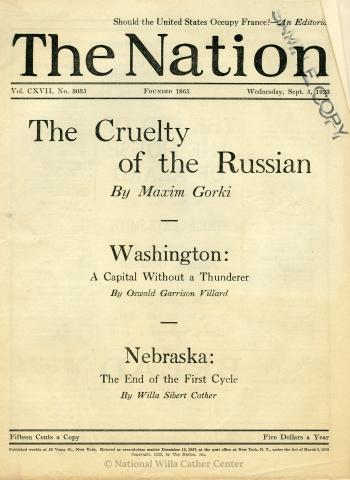

“Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle” Celebrates 100 Years

The Nation’s “These United States” series spanned from 1922-24 featuring different authors writing about 48 states. In 2003, John Leonard wrote in the Nation, upon editing a modern collection of state contributions:

“Eighty-one years ago, on April 19, 1922, The Nation launched a series of forty-nine articles by a distinguished, skeptical and contentious group of writers–novelists, journalists, educators, social workers, lawyers, unionists and maverick intellectuals–each of whom was asked to contemplate his or her state of the union. Their essays, short but not at all sweet, were collected and published in two volumes, in 1923 and 1924, as These United States, less a symposium than a remarkably evocative crazy quilt of styles and apprehensions, moods and meditations, art and anthropology, reportage and polemic.”

Cather wrote to her editor Alfred A. Knopf on August 25, 1921 that she “must get to work at once on an article on 'Nebraska' the Nation has asked me to do for their Portraits-of-the-States series.” [Cather-Knopf Correspondence, The Dobkin Family Collection of Feminism, New York, NY]

That autumn, Cather embarked on a Midwest speaking tour which included stops in Nebraska. In Omaha she admonished Nebraska’s decision to make it illegal to teach foreign language to students under the eighth grade:

“Miss Cather told her audience that one of the things which retarded art in America was the indiscriminate Americanization work of overzealous patriots who implant into the foreign minds a distaste for all they have brought of value from their own country. ‘The Americanization committee worker who persuades an old Bohemian housewife that it is better for her to feed her family out of tin cans instead of cooking them a steaming goose for dinner is committing a crime against art’ declared Miss Cather, who kept her audience laughing and gasping at the daring but simple exposition she gave the meaning of art.”

‘No Nebraska child now growing up will ever have a mastery of a foreign language," said Miss Cather, ‘because your legislature has made it a crime to teach a foreign language to a child in its formative years—the only period when it can really lay a foundation for a thorough understanding of a foreign tongue.’” [Omaha World-Herald, 30 October 1921]

These same pronouncements would appear two years later in her article for the Nation.

In a June 1 letter to Dorothy Canfield Fisher in 1922, Cather praised Fisher’s contribution in the Nation’s series, “Vermont: Our Rich Little Poor State” (May 31, 1922):

“I must say a word about your splendid article on Vermont in the Nation,— the only interesting one so far in that dull and deadly series, the only one that sounds as if it were about human people.” [Dorothy Canfield Collection, University of Vermont, Bailey-Howe Library, Burlington, VT]

In a September 21, 1923 letter to Judge Duncan M. Vinsonhaler, Cather wrote:

“Harvey Newbranch's editorial, which you were so good as to send me, fills me with pride and pleasure. That Nation article was a labor of love; I only did it because I was afraid the editors might give it to someone who would do a real-estate article. I am very happy to feel that people who know much more about the history of the state than I do, are satisfied with my presentation of it.” [Willa Cather Papers, 1899-1949, in the Clifton Waller Barrett Library (6494), Newberry Library, Chicago, IL]

Harvey Newbranch (1875-1959) was the Pulitzer Prize-winning editor of the Omaha World Herald (from 1906-1946) and a friend of Cather’s at the University of Nebraska. Cather refers to the September 6, 1923 editorial that he wrote about her contribution to the series, which appeared as the lead editorial in that issue. [You can read a complete transcription of the editorial below.]

Two years earlier he had written in a November 1921 editorial, after Cather’s Nebraska presentations:

“Nebraska may well be proud of Willa Cather. She is sprung from its soil. She was taught in its schools. Her soul was given texture and form on its sweeping plains, under its clear skies, in contact with the hardy pioneers who subdued its frontiers. And her voice, at once brave and tender in its sympathy, is like a refreshing breeze from its illimitable spaces, carrying invigoration for every human life where cowardice and cant and hypocrisy have wrought their soul-destroying work.”

“Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle” is a hymn to the state’s then-recent past, its immigrants and customs. It is about the importance of a place and its people—the traditions and prairie landscape of the Great Plains that Cather loved and knew as a young woman, and that would later infuse much of her fiction. It is arguably statist and yet with a firm nod towards the great diversity of immigrant culture within its borders, and the state's contributions to the nation.

As Cather wrote in praise of the importance of native language, tradition, and culinary customs:

“Our lawmakers have a rooted conviction that a boy can be a better American if he speaks only one language than if he speaks two. I could name a dozen Bohemian towns in Nebraska where one used to be able to go into a bakery and buy better pastry than is to be had anywhere except in the best pastry shops of Prague or Vienna. The American lard pie never corrupted the Czech…”

Her essay ends:

"The population is as clean and full of vigor as the soil; there are no old grudges, no heritages of disease or hate. The belief that snug success and easy money are the real aims of human life has settled down over our prairies, but it has not yet hardened into molds and crusts. The people are warm, mercurial, impressionable, restless, over-fond of novelty and change. These are not the qualities which make the dull chapters of history."

Read the full transcript of “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle” on the Cather Archive website

"Willa Cather's Nebraska" — September 6, 1923 — Omaha World Herald

“Willa Cather’s Nebraska” by Harvey Newbranch, editor of the Omaha World Herald

Any person inclined to feel discouraged about Nebraska should read Willa Sibert Cather’s 4,000 word essay on this state, published in the Nation, under the title, “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle.”

Miss Cather’s article doesn’t ‘put Nebraska on the map” as Babbit would glibly phrase it. It would be literary sacrilege to speak of so fine a composition in the hackneyed terms of the ‘booster’ enthusiast. It does, however, give this commonwealth cause to hold up its head as a worthy member of these United States. It is an impartial estimate of our spiritual state following the passing of those splendid men and women, the sturdy pioneers who brought our fruitful acres under subjection and with whose going the first phase of Nebraska’s history ends. It does not attempt to hide the smudges that are in the picture, but it is filled with faith and hope that we shall build worthily upon the foundation which the fathers have laid for us. It is written by one who believes in Nebraska and is the sort of thing that we may be proud to have others read of us.

Willa Cather grew from girlhood to maturity in Nebraska. Although her home is now in that mecca for the literary artisan, New York, we cannot doubt that her heart is still in Nebraska. If we are to judge from her previously published material she still feels herself flesh of our flesh, bone of our bone. Her girlhood in south central Nebraska, where she witnessed the struggle of the builders of this state, has left her with an understanding that it is given only to genius to have. She came to love the soil and the people who had transplanted their lives from the east, the south and from far across the Atlantic to our fertile, but tough and sometimes drouth-stricken acres. She has retained a sympathetic touch with Nebraska that will make her always distinctly “one of ours.” It is fortunate that Nebraska has Willa Cather, the daughter of a pioneer, to sing its epic, a portion of which she had already done in fiction.

• • •

One cannot compress much of history into 4,000 words except the writer is a master craftsman, but that is what Willa Cather is. Briefly but deftly she sketches a panorama of the change from coppery-brown prairie, peopled only by bison herds and bands of Indian hunters and wild fowl, into the great agricultural commonwealth of today. One sees the first isolated settlements spring up at Bellevue, Omaha, Brownville, Nebraska City, clinging to the banks of the Missouri, their only means of contact with civilization; the long wagon trains of the Mormons, following their scouts into a wilderness to escape religious persecution; the gold hunters following the old Indian trails; the freighters who maintained the lines of communication by ox train between the Missouri and the mining camps of Colorado and the Mormons of Utah; the railroads and the settlers pushing into the west, throwing up their sod houses on the open range.

Recently the has been formulating a cult dedicated to the propagation of the ideas that “nothing good can come out of Europe,” that only grief can follow association with European peoples. It would be good for the soul of the followers of this cult to read Miss Cather’s article. It might surprise them to know that Nebraska was largely built by foreigners, Germans, Czechs and people from the Scandinavian countries. She quotes census figures to show that as late as 1910 foreign American stock in Nebraska outnumbered native American stock in Nebraska about three to one.

Does it frighten her, this woman of Virginia parents who pioneered Nebraska, that this foreign influence is breaking down our Americanism? It does not. She sees it in hope for a regeneration of our spiritual ideals. Says she:

“When I stop at one of the graveyards of my own county and see on the headstones the names of fine old men I used to know: ‘Eric Ericson, born Bergen, Norway…died Nebraska’; ‘Anton Pucelik, born Prague, Bohemia…died Nebraska.’ I have always the hope that something went into the ground with those pioneers that will one day come out again. Something that will come out not only in sturdy traits of character, but in elasticity of mind, in an honest attitude toward the realities of life, in certain qualities of feeling and imagination…It is that great cosmopolitan country known as the middle west that we may hope to see the hard molds of American provincialism broken up; that we may hope to find young talent which will challenge the pale proprieties, the insincere conventional optimism of our art and thought.”

• • •

The “other side of the medal, stamped with the ugly crest of materialism,” she sees in a coming generation which tries to cheat its aesthetic sense by buying things instead of making anything. She deplores a tendency in the state university to magnify the importance of those studies which have to do with “the game of getting on in the world’ at the expense of the classics and humanities. But she does not despair of the future of her alma mater. She hopes, nay even predicts, that there will come a revolt against ‘all the heaped-up machine-made materialism” of the age. ‘They will go back to the old sources of culture and wisdom,’ she says, ‘not as a duty, but with burning desire.’

The generation ‘now in the driver’s seat which wants to live and die in an automobile’ perhaps saddens her a little, but it does not shake her faith in Nebraska. She shows it in this splendid peroration:

‘Surely the materialism and showy extravagance of this hour are a passing phase! They will mean no more in half a century from now than will the hard times of twenty-five years ago—which are already forgotten. The population is as clean and full of vigor as the soil; there are no old grudges, no heritages of disease or hate. The belief that snug success and easy money are the real aims of human life has settled down over our prairies, but it has not yet hardened into molds and crusts. The people are warm, mercurial, impressionable, restless, over-fond of novelty and change. These are not the qualities which make the dull chapters of history.’