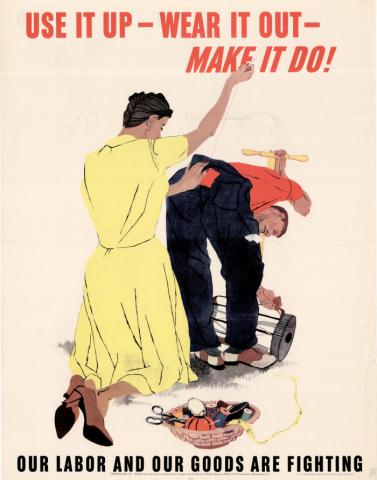

Annotations from the Archives: Use It Up

Use it up,

Wear it out,

Make it do,

Or do without.

This week, the Red Cloud Opera House Gallery opens the traveling exhibit Thrift Style, a collection of materials and textiles that are related to the Depression-era practice of reusing flour, sugar, and feed sacks to create clothing, quilts, and other necessities. Organized by the Historic Costume and Textile Museum of Kansas State University, the show provides a nostalgic view into American ingenuity, sensibility, and optimism during a challenging time of economic hardship and war.

The reuse of feed, flour, and sugar sacks was a cost-saving and resource-saving approach employed by homemakers during the period encompassing both world wars, roughly 1915–1945. However, measures like these weren’t new to the people of the Great Plains. Settlers to the wide-open West have always struggled to do more with less—whether the end result provided for daily needs or for amusement. Andrew Yarrow's book Thrift: The History of an American Cultural Movement, identifies a direct line of thinking from New England Puritan thought to U.S. government war-time thrift programs, folding in numerous social movements that encouraged thrift as "a fundamental of success, prosperity, and happiness" (30).

Nonetheless, the thrift movement was not dominated by crackpots or reactionaries who simply could not abide a modernizing America . . . . Rather, it was a generally thoughtful, broad-based effort that brought together elements of Progressivism and Protestantism, social reform and social reaction, populism and the precepts of finance capitalism. The thrift movement called for stewardship and investment, and created a big tent that included individuals as different as bankers and Boy Scouts. It addressed myriad social problems from poverty and debt to the exploitation of the common man and the environment . . . . all the more worth hearing and understanding [today]. (Yarrow 14)

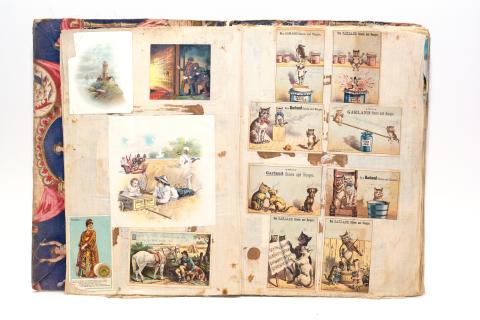

Everyday examples of thrifty living in the 1880s are easy to find, and in our collections, nearly every collection contains an example of creating something from scraps, leftovers, or giveaways. Advertising cards—and scrapbooks made up of those cards—were extremely popular as a form of education and entertainment for both children and adults. Willa Cather created several of these using advertising cards and cards of merit from both school and Sunday school. In Willa Cather’s albums, the characters on the cards were sometimes given names of friends or siblings, as though stories were being created or acted out based on the scenes.

In a letter to Catherton neighbor and lifelong friend Lydia Lambrecht, Willa Cather wrote, “. . . I have several times sent to Nebraska packages of cards like those I am sending to you. While my mother lived, she liked me to send my Christmas cards to her. But now there are very few people who care about “picture cards”, as we used to when we were children. Movies and illustrated magazines have done away with all that. Children never make “scrap books”, as we used to do” (February 20, 1943).

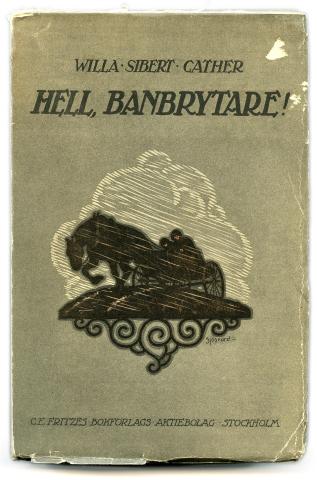

While never as flashy or entertaining as advertising cards, flour-sacks were ubiquitous on the Plains, as Cather makes clear as she portrays them in her fiction. Their utility as a vehicle for collecting or transferring goods was naturally of primary importance on the frontier. Cather wrote to her family, “The new Swedish edition of “O Pioneers” is one of the handsomest books I have ever seen. I have ordered several from Stockholm, and when they come I will send Mother one. The Swedish looks so funny to me, Mother; like Petersons’ newspapers I used to bring home from Mr. Crowley’s in a flour sack, on horseback. You remember?” (December 6, 1919).

Later on, perhaps when no longer useful for toting, the flour sacks could be turned into other items: clothing for children, pieced quilts, aprons, doll clothes. Anna Sadilek Pavelka, the Webster County woman who was immortalized as Ántonia Shimerda in Cather’s novel My Ántonia, was locally famous for her handiwork—much of it utilizing scraps and fabric from sugar and flour sacks. Our collections boast several quilts that were handmade by Anna Pavelka, as well as a number of other small items. One of our quilts is displayed with the traveling exhibition, along with flour sacks and another quilt top from the Webster County Historical Museum. A special piece that has never before been displayed is a child's apron, made of flour sacking by Pavelka for her great-granddaughter. For Pavelka and her large family (ten children!), a thrifty mindset was a way of life!

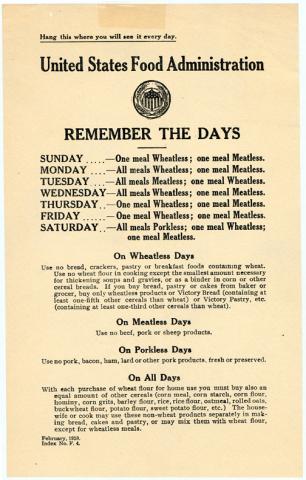

By the time that World War 1 was in full swing, the U.S. government had begun organizing and advertising the need for economy. Herbert Hoover, long before he became President during the Great Depression, was just beginning his life in public service when he was made head of the U.S. Food Administration. This WW1 food rationing program encapsulated a number of initiatives like “Meatless Monday” and “Wheatless Wednesday” to encourage Americans to save food.

In "Roll Call on the Prairies," Willa Cather describes the ways that war rationing affected the entire country—but she was quick to note the oversized contributions of Great Plains communities.

In the first place, diet and cookery, the foundation of life, were revolutionized (city people could never realize what this means in the country and in little towns). All the neighbor women began to tell me how to make bread without white flour, cakes without eggs, cakes out of oatmeal, how to sweeten ice cream and puddings with honey or molasses. When my father absent-mindedly took a second piece of sugar at breakfast, he felt the stony eyes of his women-folk and put it back with a sigh. My old friends could talk to me all day about the number of hot breads they could make without wheat flour, about rice bread, and oatmeal loafs, and rye loafs. All winter long they had experimented with breadstuffs. In New York we merely took a new kind of bread from the baker—hoping it wouldn't be worse than the last—and grumbled at the grocer because he wouldn't give us more sugar. But in the little towns, Hooverizing was creative and a test of character as well.

As you next read through Cather's words, perhaps give a moment to think of thrift as not only a personal value of the characters, but as a cultural movement—one that Cather experienced many times and in many forms throughout her life. And if you're able to visit the Red Cloud Opera House gallery, we hope that you'll enjoy the Thrift Style exhibit. It will be on display in the gallery until March 8, 2025.

A special thanks to the Webster County Historical Museum for lending their "Hearts and Butterflies" quilt top and their historic flour and sugar sacks. While the County Museum is closed for the winter, the National Willa Cather Center is pleased to partner with director Teresa Young. "It gives more people a chance to see what is available at the Webster County Historical Museum as well," says Young, especially those who might not otherwise get a chance to visit.

We also want to recognize Mark and Paula Daharsh, Skeeter Omel and Steve Skupa, and the family of Antonette Willa Skupa Turner for their donations of Anna Sadilek Pavelka materials which have greatly enriched the Thrift Style exhibition. Donations of materials that provide context for our historic sites and the lives of those who settled Webster County are always of interest for our collections. To discuss a possible donation, please contact director of collections and curation, Tracy Tucker, at ttucker@willacather.org.