Annotations from the Archives: Cather Press Clippings

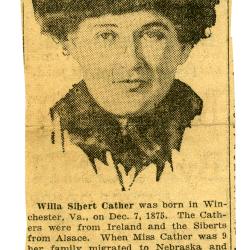

As has been noted so often before, there exists within Willa Cather so many interesting dualities. She was intensely engaged with her small hometown, even as she became a traveler of the world; she was down-to-earth and plain spoken, but she enjoyed the niceties that her career afforded her—the fine clothes, the fascinating company. The Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Collection contains even more evidence of these dichotomies in Cather's nature. A large collection of Cather's press clippings and reviews are evidence that, though Cather was an intensely private person who was careful to create boundaries around both her work and leisure time, she was also an active marketer who understood the business of publishing and the need to be "known" by the general public.

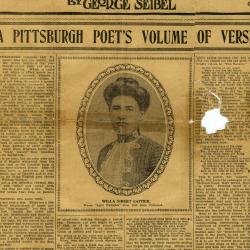

We know from Cather's correspondence that she was a dedicated reader of her press, and that she often saved and sent home clippings for friends and family. Occasionally, Cather adds a handwritten note to explain her thoughts on the piece, but more often, the clippings bear just a heavy inked bracket or hash mark to indicate the most pertinent portion of the review or article. Our collections include hundreds of such clippings, some collected in scrapbooks by Carrie Miner Sherwood, and others retained by friends and family and donated to our archives later. Taken together, they provide a useful snapshot of Cather's and Cather's publishers' efforts to keep her name in the public eye.

Recently, we added the September 1931 issue of Good Housekeeping, featuring a Leon Gordon portrait of Willa Cather and a profile by Alice Booth, acknowledging Cather as one of "America's Twelve Greatest Women." A distinguished-looking Cather, in a rich burgundy sleeveless gown, gazes directly at the viewer from the pages. "This is the ninth portrait and biographical sketch in Good Housekeeping's series of America's twelve most distinguished women," the magazine wrote. Other women in the series included another Nebraska native, social worker Grace Abbott, as well as Helen Keller, Jane Addams, opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink, and Mary E. Woolley, a professor, reformer, and the president of Mount Holyoke.

Despite the august company, Cather was unhappy with the experience. In 1944, she turned down another such honor. "I certainly appreciate your interest . . . . I realize that you pay me a friendly compliment when you include me in the list for American Portraits. . . . Some twelve or fifteen years ago I was one of the unfortunate women, selected by a distinguished committee, who appeared in full page portraits in Good Housekeeping. For me the result was a correspondence that was very burdensome. Hundreds of letters poured in upon me, and a great many of them required courteous personal answers. Old schoolmates, distant relatives, kindly people whom I had known in some part of the United States. . . . From this experience I learned a lesson. The better the advertising, the worse it is for me. It disturbs my life and my work too much."

Sitting for a portrait was, indeed, a lengthy process. When Cather sat for a portrait by Leon Bakst for the Omaha Public Library, it required twenty sittings, and Cather feared that the "thoroughly modern" Bakst would create a likeness that the Omaha patrons would not like. During the sittings, Thérese Bonney photographed Cather and Bakst in the studio, a photo that would later be used to promote both the painting and Cather's writing more generally around the world, but most heavily here in Nebraska. "To let young people know that recognition is given to art as well as to more material enterprises," the club women of Omaha commissioned the piece for $2,000.

Cather was more inclined, even before the Good Housekeeping experience, to use photographic portraits for promotion. In 1915, in response to a request for a photo to accompany The Song of the Lark, Cather writes to Houghton Mifflin's Alverda Van Tuyll, "In the first place, let me tell you how delighted I am that you get a thrill out of the story, and in the second, let me tell you how I lament the costom [sic] of publishing photographs of authorines. . . ." Cather believed that candid photos were nearly useless unless taken in the right setting, and she worried too about her own appearance. "Myself, I think the public prefers to think that all authorines are tall, slender, and nineteen years of age." Ultimately, though Cather had suggested a photo taken in the cliff dwellings of New Mexico or Colorado, a studio portrait by William Hollinger was secured and used for several years.

As Cather worked to protect her personal time, she turned down speaking engagements, lectures, and even club appearances, but she was urged by her publisher, Alfred Knopf, to graciously accept at least some honorifics. In a 1932 letter to photographer Carl Van Vechten, Cather writes, "On Tuesday, I am going, unwillingly, out to Chicago to receive a 'gold medal' from several women. Alfred says one can't refuse to take a medal, no matter how little one wants it." To do so, she tells friend Irene Miner Weisz, would risk "being thought very conceited."

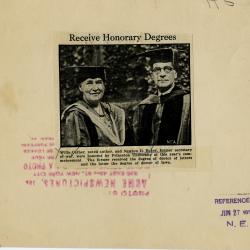

However, she did seem to genuinely enjoy collecting honorary degrees. Cather and Edith Abbott became the first women to receive honorary doctorates from the University of Nebraska in 1917, and in 1931, Cather was again the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Princeton. "Although the list of notables so honored included Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh, Frank B. Kellogg, and Newton D. Baker, the conferring of the degree of Doctor of Letters upon Willa Cather, the novelist, seemed to attract the greatest attention from those present," wrote The New York Times the next day. Photos of the Princeton ceremony, with Cather et al in their robes and hoods, spanned the globe.

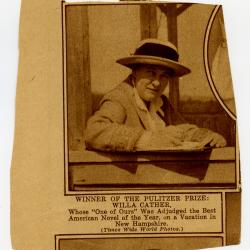

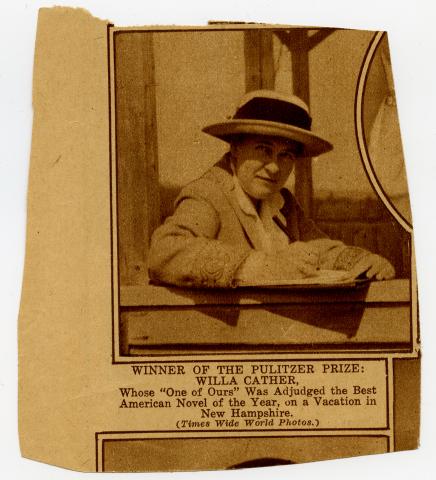

News of awards, reviews of newly published work, and even Cather's comings and goings from Red Cloud were all deemed newsworthy, and Cather frequently shared clippings with her family and friends to pass among themselves. As can be seen in some of these examples, they too began keeping her clippings from their own locale to share with Cather when they next were in touch.

Cather's press clippings are open to research. To request an appointment or learn more, please contact archivist Tracy Tucker at ttucker@willacather.org or fill out a Collections Access Request on our website.